This list contains a fraction of the historic, cultural, and natural sites that interpret the unique landscape and stories that define the nation. By engaging with these sites, we can better understand the nuances and relevancy of the past as well as recognize the importance of preserving these places for posterity.

Edmund Pettus Bridge (Selma, Alabama)

The Edmund Pettus Bridge was designated a National Historic Landmark on February 27, 2013. The bridge is a reminder of the violent attacks inflicted upon civil rights activists on March 7, 1965, a day that is referred to as “Bloody Sunday.” The televised attacks captured the nation’s attention and became a seminal moment in the campaign for voting rights in the U.S.

Gateway Arch National Park (St. Louis, Missouri)

The Gateway Arch National Park was initially established in 1935 as the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial and consisted of the Old Courthouse where the first two cases in the Dred Scott Case were litigated. In 1948, a nationwide design competition resulted in the selection of Eero Saarinen’s design of a stainless steel arch. Construction of the Arch commenced in 1963 and concluded on October 28, 1965. In 2018 the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial was re-designated as the Gateway Arch National Park to recognize the roles of Thomas Jefferson and St. Louis in the expansion of the nation, those who migrated or were forcibly transported west, and the efforts of Dred Scott to secure his freedom through the courts.

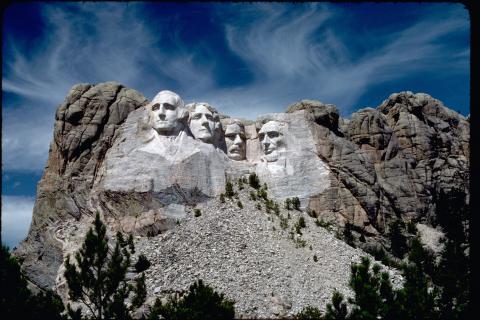

Mount Rushmore National Memorial (Keystone, South Dakota)

The Mount Rushmore National Memorial was established on October 31, 1941. Doane Robinson, the South Dakota State Historian, initially proposed the idea of creating a sculpture in the Black Hills in 1928. The South Dakota state government selected sculptor Gutzon Borglum to create the memorial and it was he who selected Presidents George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt as subjects for the memorial. Once funding was secured by the Mount Harney Memorial Association, construction commenced on the first carving on October 4, 1927 and workers completed Mount Rushmore National Memorial on October 31, 1941. The memorial attracts over two million visitors from across the nation and world every year.

Wupatki National Monument (Flagstaff, Arizona)

President Calvin Coolidge established Wupatki National Monument on December 9, 1924. The monument preserves prehistoric pueblos that date back to 900 years ago. Within the boundaries of the park are the Wupatki Pueblo, the Wukoki Pueblo, the Lomaki Pueblo, Box Canyon Pueblo, the Citadel Pueblo, the Nalakihu Pueblo, and other pre-historic ruins. The Wupatki Pueblo contained over 100 rooms and garnered substantial wealth and influence within the region. Architectural details in the pueblos indicate tribal interactions. The Kayenta, Sinagua, and Cohonina groups are associated with the settlements. For the Hopi, Zuni, and Laguna Pueblo people, among others, the settlements within the monument connect the tribes to their ancestors.

Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument (Washington, D.C.)

The Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument was designated on April 12, 2016 and serves as the headquarters of the National Women’s Party. Located near the U.S. Capitol building, the monument is a testament to the activism of famous suffragists who dedicated their lives to championing women’s equality.

Susan B. Anthony Square Park (Rochester, New York)

The Susan B. Anthony Square Park is located close to Anthony’s home in Rochester, NY. Situated in the park is a bronzed sculpture titled “Let’s Have Tea.” It depicts Anthony and Frederick Douglas engaging in a conversation as they sit across from each other. The sculpture honors their commitments to abolitionism and the suffrage movement.

Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site (Collinsville, Illinois)

The Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site encompasses the archaeological remains of the largest ancient Native American settlement north of Mexico during the Mississippian period. The site was designated a National Historic Landmark on July 19, 1964, and added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1966. It was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1982.

César E. Chávez National Monument (Keene, California)

The César E. Chávez National Monument honors Chávez’s work and legacy within the farm workers movement and is located on the property of Chavez’s home which also served as the headquarters of the United Farm Workers Union. The monument was established in 2012 and is currently in the process of expanding to include more exhibits and educational resources for visitors.

Charles Young Buffalo Soldiers National Monument (Wilberforce, Ohio)

The Charles Young Buffalo Soldiers National Monument was established on March 25, 2013 to honor the achievements of Colonel Charles Young. In the late nineteenth century, Young began a distinguished career in the military and eventually became the first African American national park Superintendent in 1903. The monument consists of the former home of Colonel Young and 60 acres of surrounding land.

Freedom Riders National Monument (Anniston, Alabama)

The Freedom Riders National Monument was established on January 12, 2017 to preserve the story of the first interracial coalition of thirteen activists who challenged the continued segregation of interstate busing in 1961 by riding buses into the south. A group of white segregationists attacked the bus and threw a firebomb into the vehicle in order to trap the riders inside. The monument consists of the Greyhound Bus Station where a white mob that included the Ku Klux Klan began attacking the bus, and the site where the bus exploded as a result of a firebomb.

Grand Canyon National Park (Grand Canyon, Arizona)

The Grand Canyon National Park was established on February 26, 1919. Approximately 5.9 million people travel to the 1,218,375 acre park that encompasses the famous gorge, river tributaries, and adjacent lands. For more than 13,000 years, people have populated the Grand Canyon and its surrounding lands. Today, eleven different Indigenous tribes continue to recognize the site as a homeland and preserve the cultural links developed by their ancestors. There are also over 500 species of animals and 1,500 plant species across the park.

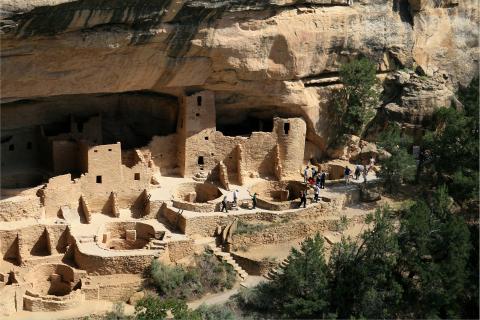

Mesa Verde National Park (Mesa Verde, CO)

Mesa Verde National Park was established in 1906 to preserve the history and cultural resources of the Ancestral Pueblo people who inhabited the region from 550 to 1300 CE. The park consists of 5,000 archaeological sites, including cliff dwellings, masonry towers, farming structures, and mesa top sites. The park was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1978.

Pullman National Monument (Chicago, Illinois)

The Pullman National Monument interprets the 1894 Pullman Strike and Boycott, the emergence of the first planned company town, the rise of George Pullman, and the experiences of the laborers. It was established as the first National Park Service unit in Chicago on February 19, 2015 and had previously been named a National Historic Landmark on December 30, 1970. The monument encompasses the former Pullman Palace Car Works factory and administration building, the Hotel Florence, Arcade Park, and the Greenstone Church.

Reconstruction Era National Historical Park (Beaufort, South Carolina)

Reconstruction Era National Historical Park was established as a monument in 2017 to dispel inaccurate information about the Reconstruction Era and encourage visitors to recognize its many complexities. The park consists of the Old Beaufort Firehouse, Camp Saxton, the Brick Baptist Church, and the Penn Center. The signing of the John D. Dingell, Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act, on March 12, 2019, re-designated the monument as a national historical park and established the Reconstruction Era National Historic Network.

Golden Spike National Historical Park (Promontory, Utah)

The meeting of the Central Pacific Railroad and the Union Pacific Railroad that resulted in the joining of 1,776 miles of rail was first memorialized as a non-federal national historic site on April 2, 1957. On July 30, 1965, the federal government established Golden Spike National Historic Site. It was re-designated as Golden Spike National Historical Park in 2019. While the original tracks laid at the junction were removed and used to support World War II efforts the park continues to preserve other physical remnants of this technological phenomenon.

National September 11 Memorial and Museum (New York City, New York)

The National September 9/11 Memorial and Museum honors the lives of the 2,983 people killed on September 11, 2001 and February 26, 1993, and those who risked and sacrificed their lives in the aftermath of the attacks. The 9/11 Memorial lists the individual names of the 2,977 people killed at the World Trade Center site, the Pentagon, and Shanksville, Pennsylvania on 9/11 and the six people who died in the bombing of the World Trade Center on February 26, 1993. The museum helps visitors learn about the history of the attacks through collections of material objects, photographs, artwork, and personal narratives.