The 1893 World’s Fair and the First Ferris Wheel

The original Ferris Wheel at the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, Illinois, 1893.

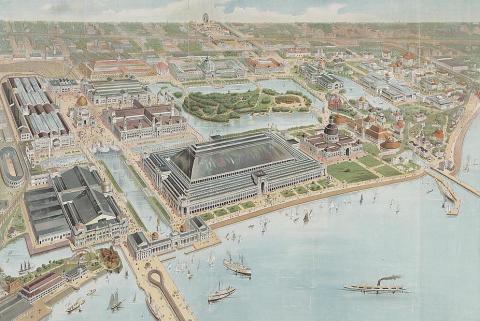

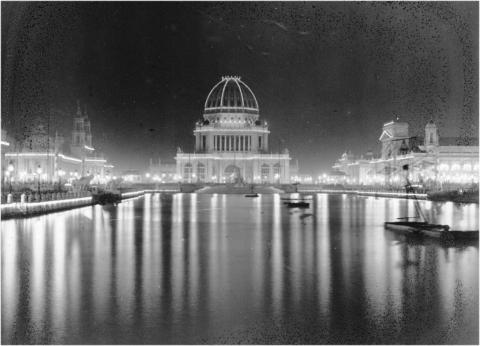

The World’s Columbian Exposition, located in Jackson Park along Chicago’s waterfront, opened to the public on May 1, 1893. Also known as the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, the six-month event commemorated the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s 1492 expedition to the Americas. The fair was one in a series of international expositions beginning with London’s 1851 Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations. World’s fairs were intended to demonstrate the cultural, technological, and imperial accomplishments of the host nation, and they drew exhibitors and visitors from around the world. With around 27 million admissions, the Columbian Exposition was one of the few fairs to turn a profit.

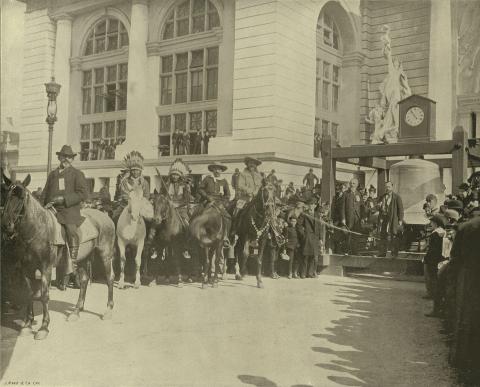

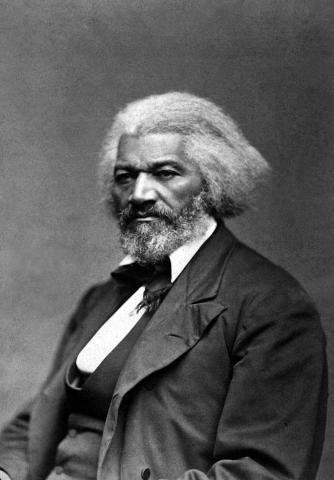

This teacher’s guide provides an overview of the exposition and its connections to major historical themes of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, including urbanization and architecture, technology and leisure, colonialism/imperialism and Indigenous resistance, racial segregation and Black activism, and women’s rights and representation. EDSITEment offers a companion lesson plan, A Spectrum of Perspectives: The Gilded Age and Progressive Era Through the Lens of the 1893 World’s Fair, designed for grades 9-12.

Guiding Questions

How did the Columbian Exposition serve as a microcosm or lens for the Gilded Age and Progressive Era?

How did the Columbian Exposition showcase exclusion and inequality?

How did the Columbian Exposition showcase activism and resistance?

What is the relationship between technology and power?