Media and Communication Technology in the Making of America

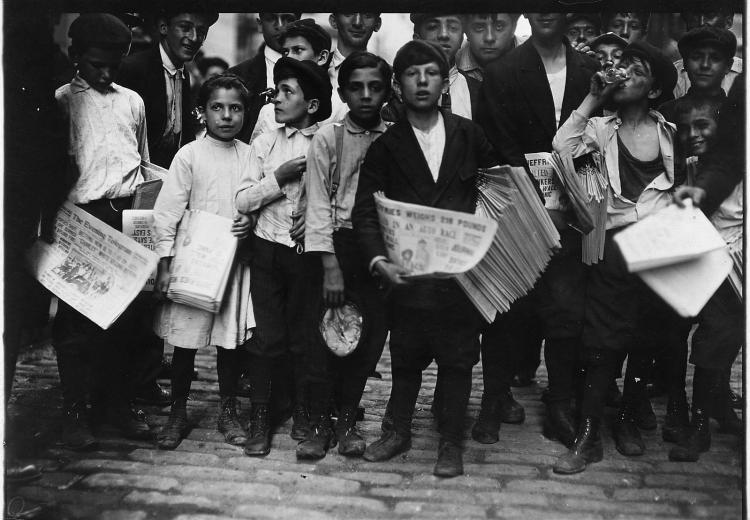

Newsboys and newsgirl in New York City getting afternoon papers (July, 1910).

The National History Day® (NHD) 2021 theme, Communication in History: The Key to Understanding, asks students to think about how people communicate with each other. Newspapers are often a key piece of the historical research process and this essay provides ideas on how to analyze and use these sources when studying media, the press, and communication technology.

When using historic newspapers and other media forms, NHD students are encouraged to consider in whose interest a report or story is published; Whose point of view is missing from the account of what happened?; By whom or for what purpose is a publication produced?; and What makes a source trustworthy? By studying innovations and events related to communication, we can begin to answer each of these questions and work toward understanding diverse and divergent perspectives across U.S. history.

This essay is framed by the compelling question “How have changes in media and technology influenced communication and civic engagement in U.S. history?”, and includes resources and lessons on media and communication technology throughout U.S. history that align with strategies for inquiry and project-based learning. The materials and learning activities included makes it possible for students to:

- Examine the role of communication in the political, social, and cultural life of people in the United States;

- Analyze the relationship between media, technology, and communication in U.S. history;

- Evaluate how news and public information—in all its forms—connect to civic engagement;

- Evaluate how media influences the public and private lives of the American people then and now; and

- Create original interpretations of historical and contemporary communication and media technology phenomena.

Print Media and Colonial America

In Colonial America, news was often transmitted orally in sermons from pulpits and in handwritten letters circulated among the elite leaders within a community. The first successful newspaper in America, the Boston News-Letter, appeared in 1704 and was the only newspaper in the colonies for 15 years. In 1719, both The Boston Gazette, a local competitor in Boston, and The American Weekly Mercury, the first newspaper in Philadelphia, emerged. The first newspaper in Virginia, The Virginia Gazette, was founded in 1736. By 1740 there were 16 newspapers in the British colonies, all weeklies. By the time of the American Revolution in 1775, some 37 newspapers thrived in business.

Each American newspaper in the colonial period had its own personality. Postmasters or booksellers operated some, but most were produced by multipurpose printers. Some were news-focused, some more literary, but nearly all followed a standard format: the style of the London papers. Early American newspapers were generally one page, comprising one small sheet printed front and back; later papers were four pages, one larger sheet printed front and back and folded once over. Typically, the first section contained foreign news, cribbed from the London or European papers. Next came news from other American colonies, followed by a bit of local news, then advertisements. All the items, including the ads, were usually very brief, limited to one paragraph or one sentence. Illustrations, while rare, often came in the form of crude woodcuts. These woodcuts used iconography to direct readers toward different areas of news. For instance, a ship represented shipping news, a house marked land transactions, and a horse indicated livestock sales and auctions.

Print Media and the American Revolution

Dating from the sixteenth century, printed announcements often took the form of broadsides, or large, single-sided sheets of paper that served as advertisements and commentary for large audiences. Not unlike present-day community bulletin boards, broadsides prior to and during the American Revolution were typically posted in public squares to reach diverse readership. The EDSITEment lesson “Colonial Broadsides and the American Revolution” asks students to consider the role of print communication by analyzing broadsides used to inform the public of actions taken by elected officials and to organize resistance against the Stamp Act in 1765, the Boston Tea Party in 1773, and the formation of the First Continental Congress in 1774. Working with these primary sources, students both analyze the timeline of significant events during this era and gain insight into how the arguments for and against revolution were organized and presented to the public. Consideration of perspective, audience, tone, and the use of evidence to support an argument are just some of the topics students can evaluate and discuss while working with these broadsides.

In 1770, Isaiah Thomas and Zechariah Fowle established the most popular newspaper of the time, the Massachusetts Spy, which boasted 3,500 subscribers throughout the 13 colonies. While Thomas, a Bostonian, initially tried to make the Spy politically impartial, he soon found it impossible to do so in the epicenter of the growing imperial crisis. Thomas’s strident Whig position was evident in his writing and in the text above the masthead: “Americans!---Liberty or Death!---Join or Die!”

Thomas’s views frequently got him in trouble with the royal authorities, as evidenced by the history behind the May 3, 1775, issue of the Massachusetts Spy. Following the clash of arms at Lexington and Concord, printers sympathetic to the call for revolution rushed to publish firsthand accounts of the battles that blamed the British forces for the violence. Under the advisement of John Hancock, Thomas smuggled his press out of Boston during the night of April 16, 1775, moving it inland to the nearby Whig stronghold of Worcester, where he set it up in Timothy Bigelow’s basement. When a supply of paper finally arrived in early May, he published his May third issue of the Spy, the first periodical ever printed in Worcester.

Readers will find Thomas’s summary far from being an objective account of the Battles of Lexington and Concord. Thomas ends the introductory paragraph by claiming that the British troops had

...wantonly, and in a most inhuman manner fired upon and killed a number of our countrymen, then robbed them of their provisions, ransacked, plundered and burnt their houses! nor could the tears of defenseless women, some of whom were in the pains of childbirth, the cries of helpless, babes, nor the prayers of old age, confined to beds of sickness, appease their thirst for blood!—or divert them from their DESIGN of MURDER and ROBBERY!

Using this primary text in class, students may ask, as a publisher would, whether Thomas had the right to include his own ideological leanings within the publication. Comparing this and other publications of the time raises questions about bias, freedom of speech and press, and the responsibility of the press to provide factual and impartial information. By analyzing point of view and the manner in which writers and publishers organize arguments, students are engaged in critical reading that aligns with change-over-time analysis and helps them recognize that arguments regarding bias and truth have a long history in media communication.

Newspapers and the Early Nineteenth Century

Newspapers flourished dramatically in early nineteenth century America. By the 1830s, the United States had some 900 newspapers. The 1840 U.S. census counted 1,631 newspapers and by 1850 the number was 2,526, with a total annual circulation of half a billion copies for a population of a little under 23.2 million people. The growth in daily newspapers was even more striking. From just 24 in 1820, the number of daily newspapers grew to 138 in 1840 and to 254 in 1850. By mid-century, the American newspaper industry was amazingly diverse in size and scope. Big city dailies had become major manufacturing enterprises, with highly capitalized printing plants, scores of employees, and circulation in the tens of thousands. Meanwhile, small town weeklies, with hand-operated presses, two or three employees, and circulations in the hundreds were thriving as well. Students can explore examples of these newspapers at the American Antiquarian Society's website.

An important and very popular daily newspaper in New York, The Sun (established in 1833), was the first so-called “penny press” paper in America, targeting the middle and lower classes. The editorial style of these papers also tended to be sensational, often featuring stories of crimes and other socially aberrant behaviors that would attract attention and sell papers. Students can examine some of the attention-grabbing rhetorical tactics used by these presses and compare them to headlines and advertisements they might see on the internet today. Aside from using newspaper sources to help students evaluate the role of media in U.S. politics and economy, they can also provide important firsthand accounts of historic events. In the EDSITEment Lesson “Evaluating Eyewitness Reports” students can investigate primary sources from the American Civil War and 1871 Chicago Fire.

Newspapers solidified communities of Americans that were not represented in positions of power in the first half of the nineteenth century. For example, newspapers owned and operated by African Americans proliferated with the rise of the abolition movement. Frederick Douglass, a notable American who broadcast his ideas via published speeches and newspaper contributions, founded The North Star anti-slavery newspaper (1847), which is featured in the EDSITEment Lesson “Debate Against Slavery”. In this lesson, students use evidence to argue why an African American print newspaper had more of an impact on the abolitionist movement than speeches given to various audiences around the country.

Women not only contributed to the labor of the nineteenth-century American press, but they also used print culture to advocate for their rights and comprised the primary consumer market for domestic magazines and trade catalogues. In the EDSITEment Closer Reading “Women’s History through Chronicling America" students can reconstruct the response to nineteenth-century women’s suffrage campaigns through newspaper write-ups.

EDSITEment’s “Chronicling America: History’s First Draft” brings together resources and lessons that incorporate the use of historical newspapers, including access to newspapers specific to multiple ethnic and racial groups. As the nineteenth century saw the arrival of immigrants from Europe, the Middle East, and Asia, newspapers in languages other than English became available. Some of the most popular languages were German, Polish, and Yiddish and you can learn more at the Humaniites magazine article “Chronicling America’s Historic German Newspapers and the Growth of the American Ethnic Press.” However, the Arabic news-printing industry began in 1883 with the publication of Kawkab Amirka, the Chinese publication The Oriental, or, Tung-Ngai San-Luk, released its inaugural issue in 1855, and Charleston’s South Carolina Leader, an African American newspaper, began publication in 1865.

Of course, there were other non-English-speaking groups living in the United States and territory that would become the United States by the end of the century. The Spanish-language newspaper El Misisipi was born in 1808 in New Orleans and in 1855, El Clamor Publico was available in Los Angeles.

With each of these newspapers, students can engage in a comparative analysis that considers audience, perspective, and how these smaller newspapers compare to national newspapers in terms of the public policy issues that are covered and arguments that are forwarded in their editorial sections.

Technological Developments of the Late Nineteenth Century

After the American Civil War, rapid advancement and proliferation of communication and media technology in the United States changed the appearance and delivery of messages for a variety of purposes from commercial to political to social. Chromolithography allowed for a quick transfer of full-color images using a grease and water technique on large stones. Not only did this type of printing kick-start a new era of mass advertising, but it also proved immensely popular with social correspondence, as seen in the rise of the postcard industry supported by a growing U.S. Postal Service.

The Second Industrial Revolution (1870-1914) brought forth advancements in technology that included electricity and telecommunication, such as the expansion of telegraph lines, the telephone, and radio communication. The EDSITEment Learning Lab collection “Innovation in Telecommunication” includes resources for learning more about Thomas Edison, Alexander Graham Bell, and the tools that made communicating across the country and oceans possible, forever changing both national and international relations. These technological developments also set the stage for the explosion of sound recording and radio transmission at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Media and the Twentieth Century

Competition between publishers and the growing influence of the press on public opinion resulted in yellow journalism—the practice of seeking out sensational rather than factual news—at the end of the nineteenth century. Perhaps the original form of “click bait” in media and journalism, the sensationalizing of events in Cuba by two New York newspaper publishers, is credited with the U.S. entry into the Spanish-American War in 1898. The EDSITEment lesson “The Spanish-American War” includes an interactive component that asks students to examine competing perspectives about the war and the role played by journalists and media at the time.

On the eve of the twentieth century, the first transatlantic radio message was transmitted, ushering in a century filled with leaps in communication technology, much of which originated with developments in military technology: radio, television, film, computers, cellular communication, and the internet.

A few forms of telecommunication technology used during times of war and to communicate with foreign governments include reporting from the frontlines on the radio, filming scenes of combat, marshaling Navajo code talkers during World War II, and dialing a red phone in the White House to speak with Moscow during the Cold War. The EDSITEment lesson “On the Home Front” looks at the importance of the radio during World War II, and “The Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962” engages students with questions about the importance of the television and communication between U.S. President Kennedy and Soviet Premier Khrushchev.

As mass media became an integral component of American culture, new jobs and forms of communication were developed. EDSITEment’s “Chronicling America: History’s First Draft” brings together resources and lessons on these various topics. For instance, during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, newspaper publishers relied on newspaper boys (“newsies”) to distribute their newspapers on city streets. Learn more about newsboys who purchased their papers and had to sell all of them to make a decent profit with resources from the Library of Congress. On the other end of the press spectrum, Joseph Pulitzer single-handedly transformed the newspaper industry and became one of the wealthiest men in America. But controversy and conflict followed him to his deathbed—including press wars and accusations of libel from President Theodore Roosevelt. Although cartoonist W.E. Hill has now been largely forgotten, he was hailed as an artistic genius who dealt in “making the world safe from hypocrisy.” Every Sunday for years, Americans eagerly awaited “Among Us Mortals,” a full page of satirical illustrations devoted to the everyday citizen.

Growth in the number of people using the telephone brought about the Hello Girls, female switchboard operators who proved to be an integral part in telecommunications at home, as well as for military operations during World War I. And of course, the invention of moving pictures made it possible to share information and communicate in creative ways. In addition to a brief timeline of developments related to the creation of film and early film houses, these newspaper articles report on George Eastman’s first camera, the first time a moving picture was projected in France, and the opening of the first nickelodeon in the U.S. in 1905.

Conclusion

Questions of bias, intent, and audience are critical when discussing the press and communication since the early days of the American republic. Further, the role of technology, the means by which history is recorded, and how information is disseminated was then, as it is now, a changing and integral part of politics, economics, and culture in the United States.

As the number of news and information producers and outlets have multiplied, the need for critical reading, viewing, and listening skills as part of civic literacy has grown. As such, the investigation of news and news publishers, as well as how information is communicated to the public, can fuel inquiry and project-based learning. The theme of Communication in History: The Key to Understanding challenges students to think about how different information is conveyed to the public. It lets them consider different ways the news is presented to audiences today and how information affects the lives of everyday citizens. Students might think critically about:

● How is news gathered, distributed, shared, and consumed?

● What impact do changes in media technology have on content?

● How do historians weigh technological change against other social and economic forces?

● What impact did law and government policy have on the press and communication?

● How have changes to media and communication technology affected freedom of the press and freedom of speech under the

First Amendment?

● What roles did news and public information play in the lives of ordinary Americans?

● How might the experience of history shed light on our experience with media today?

● How might our experience with media today shed light on our understanding of history?

Though digital and social media encompass the popular means of communication used across the world today, the issues that continue to challenge governments, citizens, and the news media—bias, truthfulness, rights, and access, to name a few—have been present throughout U.S. history. How technology influences what is communicated, by whom, and for what purpose has been woven within communication from the time of early newspapers to radios to televisions to hand-held mobile devices this century. As such, our study of issues and concerns regarding communication in history informs how we consume and produce information today and, hopefully, enables us to engage with others in the interest of listening and communicating to understand.