A Defense of the Electoral College

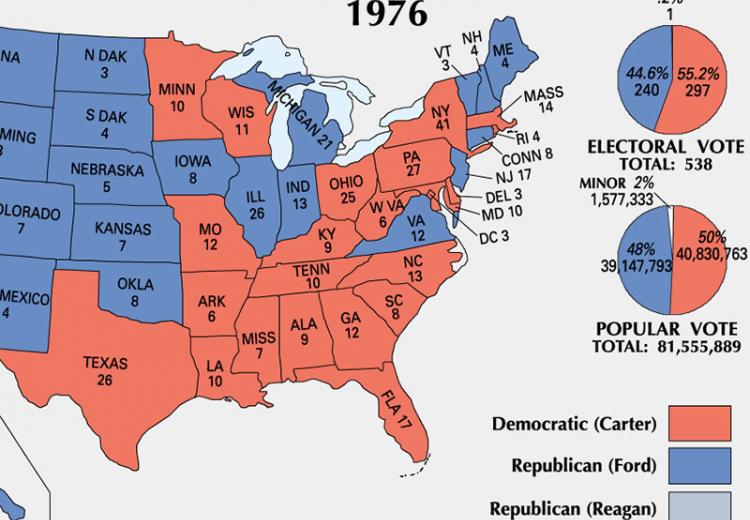

Electoral College Map for US Presidents Election, 1976.

"America's Constitutional system aims not merely for majority rule, but rule by certain kinds of majorities... All 537 of those elected to national offices — the President, Vice President, 100 Senators, and 435 Representatives — are chosen by majorities that reflect the Nation's federal nature."

— George F. Will, 2004

"To the people belongs the right of electing their Chief Magistrate; it was never designed that their choice should in any case be defeated, either by the intervention of Electoral College or by... the House of Representatives."

— President Andrew Jackson, December 8, 1829, first Annual Message to Congress

Americans elect a president through the state-by-state mechanism of the Electoral College rather than direct nationwide popular vote. Today, all but two states award all of their electoral votes to the statewide winner. Ever since Andrew Jackson was denied the presidency by the House of Representatives in 1824, some have called for its abolition. It is timely to consider the value of this vital and controversial institution devised by our founders in 1787 in the world's oldest constitution.

Three criticisms of the College are made:

- It is “undemocratic;”

- It permits the election of a candidate who does not win the most votes; and

- Its winner-takes-all approach cancels the votes of the losing candidates in each state.

Is it “Undemocratic?”

Those who call the Electoral College “undemocratic” often claim it represents the Founders’ fear of an imprudent electorate whose choice for president is best confirmed by wise and dispassionate electors. This view ignores the great debate of the Constitutional Convention between the small and large state delegates. The Congress itself reflects this struggle. Each state has two senators regardless of size, while House seats are apportioned by population.

The Electoral College evolved from a similar compromise. Fearing dominance from the populous states of New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia (which included West Virginia in 1787), small states proposed election of the president by the 13 state legislatures — each holding a single vote. Some wanted the Congress to elect our president. Large-state delegates such as Madison of Virginia naturally favored direct popular election. The Electoral College was an ingenious compromise, allowing the popular election of the president, but on a state-by-state basis. Citizens vote for president, with the winner in each state taking all the state’s electoral votes based on the number of seats that state has in the Senate and House combined. In this sense, the Electoral College is no more “undemocratic” than is the Senate or the Supreme Court. Without this large vs. small state compromise, the Convention of 1787 may not have succeeded. Without this system, states such as Wyoming, Vermont, Alaska, the Dakotas, and Delaware might never see a presidential candidate.

Majority Rule

The second criticism of the Electoral College is the most challenging. One must defend the Electoral College not as perfect, but as a better solution than the alternative, i.e., direct popular election of the president. In very close elections, victory can be denied the candidate receiving the most popular votes nationwide. This has occurred four times in 57 presidential elections: Adams (1824); Hayes (1876); Harrison (1888); and Bush (2000) — and only once since 1888. The Electoral College requires the election of a president by majorities, but state-by-state. Two political wills are thus engaged — that of the citizenry of each state, and that of the fifty states acting together. As a “nation of states”, this is part of American federalism. In 53 of 57 elections, this state-by-state system has meant that the winner build support across the nation, not in just a handful of large urban areas.

Those who would abolish the Electoral College advocate using a simple majority vote rule, i.e., the candidate receiving fifty percent plus of the popular vote is the victor. However, often no one receives fifty percent of the national vote because of third-party candidates such as Roosevelt and Debs (1912); Wallace (1968); Perot (1992); and Nader (2000). In the 57 presidential elections since 1789, no candidate received fifty percent of the vote on 18 occasions, including Lincoln (39.7% —1860); Wilson (41.8% — 1912); Truman (49.6% —1948); Kennedy (49.7% —1960); and Clinton (43% — 1992, and 49% — 1996) to name the most famous “minority presidents.” In contrast, all won a majority of the states’ Electoral College votes!

National majorities—The Electoral College creates a national majority for new presidents regardless of the popular vote margin. Reflecting the will of majorities in the fifty states, the College legitimizes the result. A sharply divided America gave Lincoln only 39.7% of the vote in 1860. However, Lincoln won 180 electoral votes — more than double the second place finisher, Breckinridge. This gave his election legitimacy at a critical moment in American history. Moreover, if America used direct elections, many more “third party” candidates would arise to render U.S. election vote margins even more inconclusive than in the past. Most third party candidates receive no Electoral College votes. In 1992, Ross Perot received 19% of the vote but no electoral votes.

Salutary focus—In a continental republic of 310 million people, the Electoral College discourages political atomization and focuses the minds of our citizens on two main candidates. Look at the scene today. Senator Sanders ran for the nomination of the Democratic Party, even though he is not a member of that party. He is a Socialist.† Mr. Trump was running for the Republican nomination even though his allegiance to either of party has been tangential. Sanders and Trump were not running as independents because Electoral College state-by-state victory requirements require them to connect with our two-party system. This is a good thing. In sharp contrast, the multi-party parliamentary systems in Europe are replete with "coalition governments" and intractable "gridlocks". Self-rule is hard. "Simple" solutions can beget complicated and even harsh results.

Are votes wasted?—The third criticism is that the “winner-takes-all” provision cancels the votes not cast for a state’s presidential choice. For example, Virginia votes cast for Mondale in 1980 were “cancelled” because all 13 of its electoral votes were given to Reagan. In fact, all elections have this effect given that there is only one winner in every contest. In 1980, 37.6 million Mondale votes were "cancelled" by 54.5 million Americans who voted for Reagan. (We inherited the idea of "winner takes all" elections from the British Parliament, by the way.)

Sectional and Ideological Divisions

The abolition of the Electoral College would have significant negative impacts on our political system.

- A President would no longer be elected by the collective will of the fifty states. Small states like Delaware might be wholly ignored.

- Candidates would tend to campaign in urban areas, no longer seeking to “win statewide.” This might alienate millions in small towns and rural states such as Iowa, Wyoming, and Alaska.

- A focus on urban areas and away from statewide politics would undermine a two-party system that serves our continental republic well. A splintered and incoherent set of regional and issue-oriented parties would likely spring up. Atomization at the presidential level would be sure to spill over to our state legislatures and Congress. They might move from binary to multi-party “governing coalitions” — as fragile, ineffective, and short-lived as those in most European parliamentary systems today.

- The number of presidential candidates would rise sharply — not to win, but to deny any candidate fifty percent of the vote. This would lead to a national run-off election with political deal making and ballot litigation that would make Florida's 2000 recount seem like a minor dust-up. Recounting Florida was grueling; a national recount of 100+ million ballots is impossible! Finally, citizens of small and rural states — ignored by presidential campaigns — might consider leaving a “union” that no longer valued their voices or votes in choosing a president. The historic small vs. large state constitutional compromise of 1787 would be dissolved. Forces of disunity the founders sought to avoid would arise. We have enough of that already.

Conclusion

The founders’ Electoral College is a unique republican mechanism. It creates presidential majorities, engenders national presidential campaigns, and maintains a robust federalism, which operates most effectively within a strong two-party system. When someone says, “Let’s abolish the Electoral College,” it is fair to ask, “With what would you replace it, and how would the new system affect American federalism, our two-party system, and the unity of the United States? Removing one gear from a watch affects the entire mechanism.

Student Questions

Print the essay. Read it at least twice, making notes on the margins of the paper to identify the main elements of the essay.

- How does the title prepare for what follows in the essay?

- What purpose is served by the quotations at the head of the essay?

- Does the opening paragraph have a thesis? If so, what is it?

- Why does the author begin with criticisms, rather than praise, for the Electoral College?

- How does the author counter the “undemocratic” argument? What is his view of democracy?

- How does the author counter the argument that the College violates the principle of majority rule?

- In order to make his case, the author argues that the abolition of the College would have dangerous consequences. What are they? What do you think about this line of argument?

- Compare the conclusion with the introduction of the essay, especially the first sentence. What do you notice about the connection between the two?

- Make your own argument for or against the Electoral College.

† [Editor’s Note] Sen. Sanders has served Vermont as an independent since 2007, caucusing with the Democratic Party. He has described himself as a democratic socialist, including during the 2015-2016 presidential campaign.